Diese Diashow benötigt JavaScript.

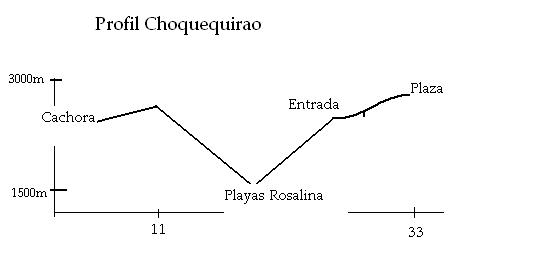

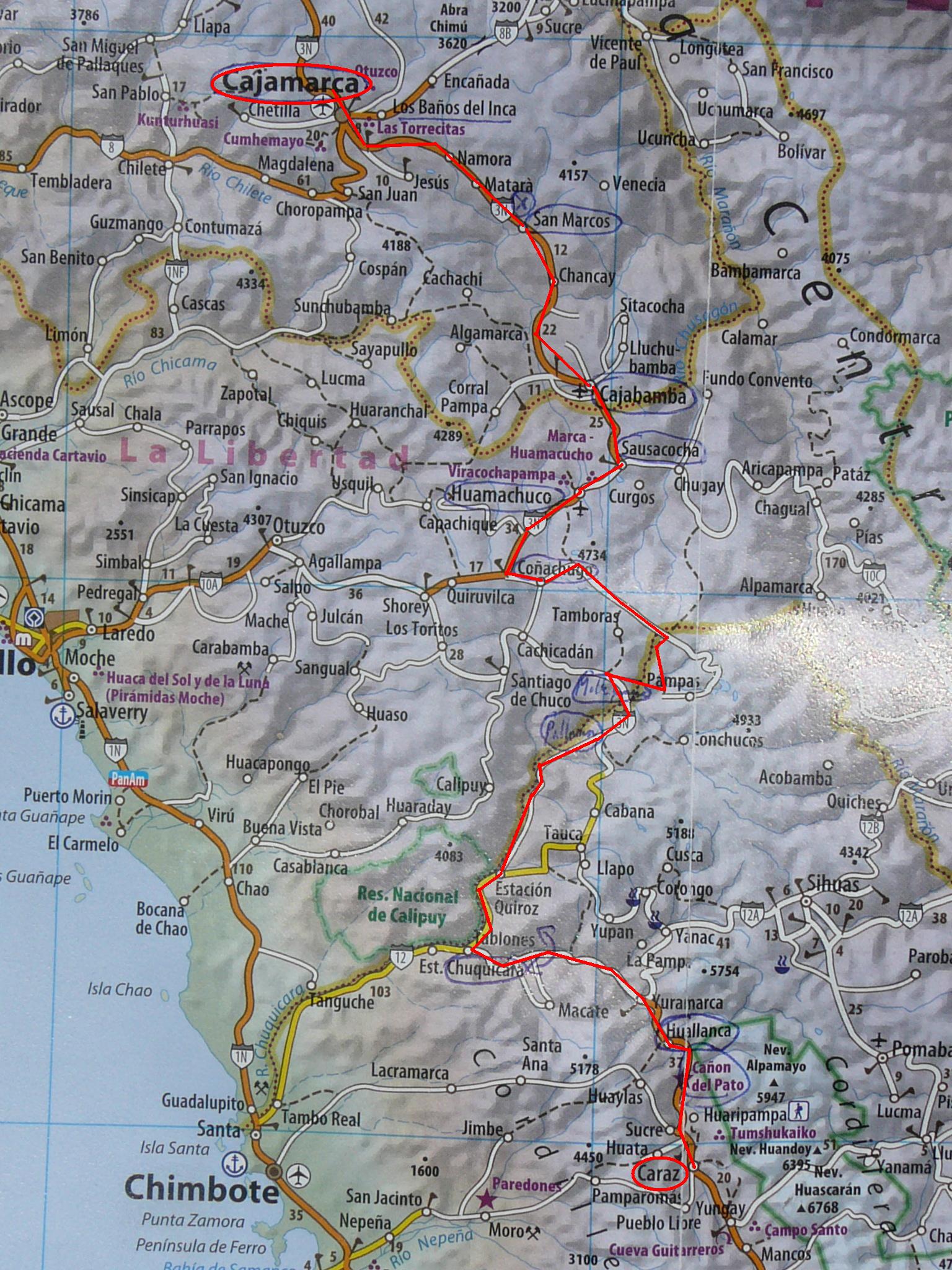

These last days had completely spoilt a set of brake pads. It was good to have new ones for the long descent from 3200m (Pallasca) down to 500m (Chuquicara). In spite of the strong head wind, the temperature was at 40°C and the air was so dry that a road worker, asking me for

un aguacito emptied my one-liter bottle at once. (I got another one handed over from a passing car later).

Water was a severe problem in all villages of this region: they generally shut down the public supply during the night and -in case of shortage- even during day time. You realize the immense value of water opening the tap and nothing happens…

I’ll never forget the beautiful scenery of this desert valley: the rocks were shining in black, brown, red, yellow, rich in minerals.

Arriving with the darkness at the few huts of

Chuquicara, I met the world cyclist

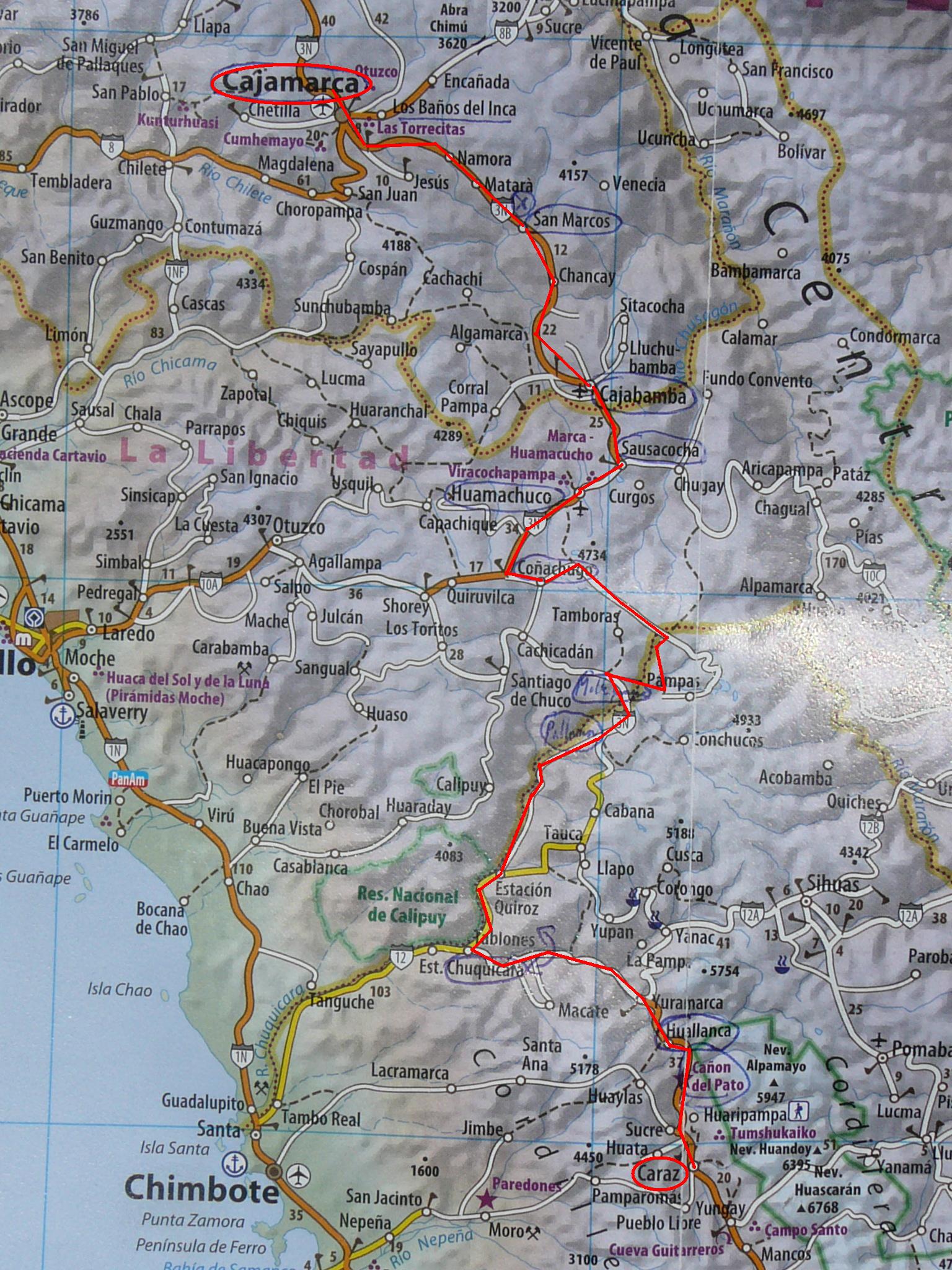

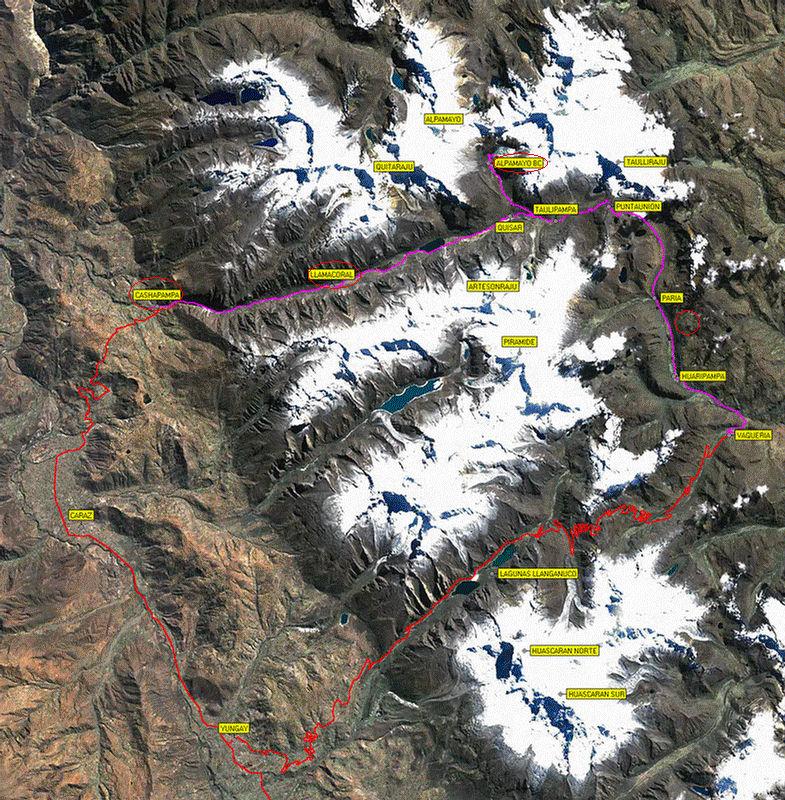

Henrik, cycling already for 3 years. We spent a superb evening having four beers and an interesting conversation about our experiences with the cultural differences here, and were friendly invited for the night on two mattresses on the earth floor nearby. He headed for the coast the next morning, while I went for the famous

Cañon del Pato, a collection of tunnels digged into hard rocks and steep hillsides.

Leaving

Huallanca, I met the google street car – they got a nice picture. I often wondered that, especially in Peru, there are still white spots: google maps and OSM miss a lot of villages and the few paper maps you may find (only foreign publishers) are full of mistakes, confounding town names, indicating wrong distances or altitudes or marking crossroads as villages. It is kind of comforting that even nowadays in our controlled world, there is still free space for discovery…

I arrived the calm and lovely mountaineer town

Caraz the next evening.

Since Cajamarca I’ce cycled for 495km, climbing 8400 altitude meters.