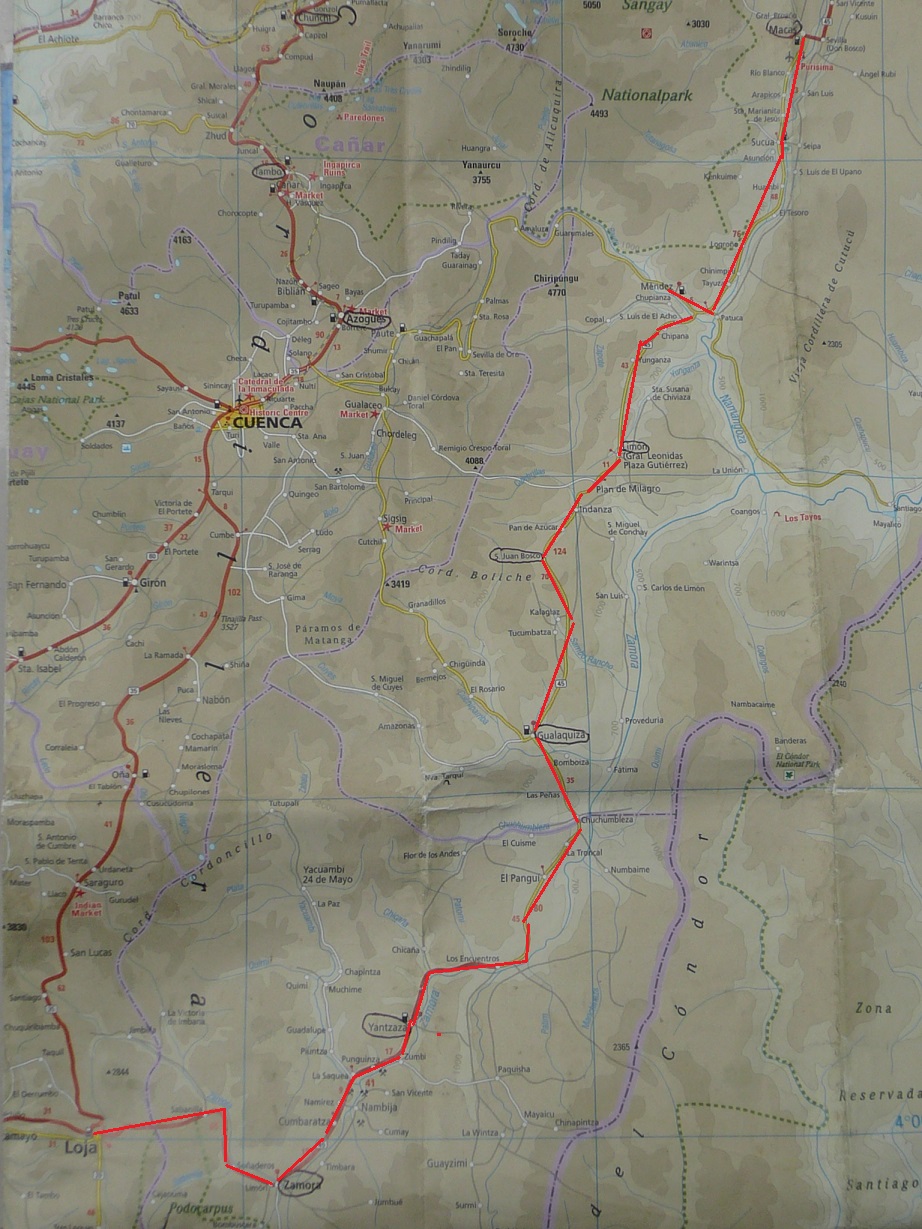

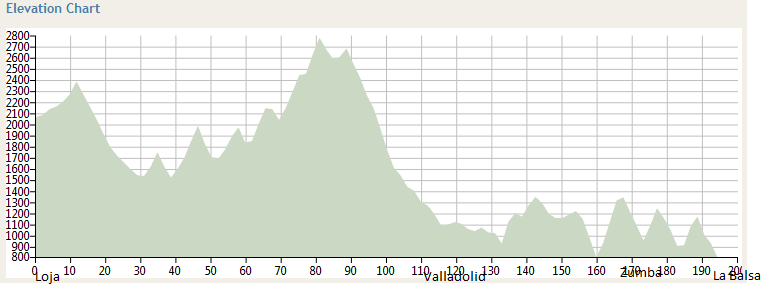

Vilcabamba liegt zwar auf gemäßigten 1500m, ist aber ringsum von hohen Bergen umgeben. Nach einem ausgedehnten Abschied konnte ich den langen Aufstieg zur Wasserscheide des Kontinents erst am nächsten Tag von Yangana im Nachbartal aus angehen: vorbei an sandigen Bergabbrüchen, deren sanfte güne Bewaldung bis zum Pass auf 2800m stetig in den kargeren Moosbewuchs der Paramó-Region überging. Immer wieder begegneten mir die selben freundlich grüßenden Truckfahrer, mal schwer mit Schutt beladen, mal unbeladen; allerdings waren die Straßenarbeiten auf der anderen Seite der Wasserscheide noch nicht sehr weit vorgedrungen: schon auf halber Abfahrt, noch vor Valladolid, harte Schotter-, dann Sandpiste, immer wieder mit meterlangen Schlammpools durchsetzt. In den Abendstunden erreichte ich Palanda, wo ich auf dem zentralen Platz das Fahrrad unter den neugierigen Augen der gemütlich vor ihren Häusern sitzenden Bewohner von seiner zentimeterdicken Erdschicht befreite. Angesichts der Etappe am folgenden Tag war das eine provisorische, vergebliche Unternehmung: Schlammbäder wechselten sich ab mit erfrischenden Flußquerungen, während sich der Pfad mit einigen kräftigen Ausschlägen nach oben und unten um die 1100 Höhenmeter durch dichtes Grün schlängelte. Am Wegrand aus Brettern gezimmerte Behausungen, deren lachende Bewohner sich gerne auf kurze, freundliche Gespräche über den Straßenbau, ihre Lebensumstände und ihre politischen Erwartungen einließen. Ich stand gerade barfuß in der Mitte einer Bachquerung, als ein vorbeifahrender Lkw anhielt, mich grüßte und mir von seinen acht glücklichen Jahren im deutschen Transportwesen erzählte. Es machte mich froh, mit seinen begeisterten Augen auf mein Heimatland blicken zu können (auch wenn meine Füße anschließend Eisklötzen glichen).

20km vor meinem Tagesziel, Zumba, brach die Nacht herein, am überdachten Rand eines abgelegenen Fußballplatzes schlug ich mein Zelt auf, als auf der dunklen Straße, angekündigt durch Hundegebell im Dorf, die Schattengestalt eines Radfahrers langsam vorüberzog. Rufend („somos ciclistas, yo tambien, a donde vas, quedate conmigo„) rannte ich der gespenstischen Erscheinung für etwa hundert Meter hinterher, die aber stumm und unbeirrt ihren Weg fortsetzte. Ich saß vor dem Zelt und blickte in die Stille der Nacht, als sich die Gegend plötzlich belebte: unvermittelt umgab mich eine Heerschar von Kindern, Flutlicht-Scheinwerfer gingen an und unter tausend staunenden Fragen war ich eingeladen zu einer nächtlichen Fußballpartie. Herzlich war der Abschied und herzlich das Wiedersehen mit Wilmer und Paul am nächsten Morgen.

In Zumba traf ich Ron aus Colorado, das nächtliche Phantom, gemeinsam radelten wir das steinige Auf und Ab durch das einsame Land bis zum kleinen Grenzübergang bei La Balsa. Mit den Stempeln in unseren Pässen waren wir in Peru und glücklich auch wieder auf Asphalt.

Seit Loja: 204km und 4860 Höhenmeter aufwärts.

Courtesy of bikeroutetoaster.com