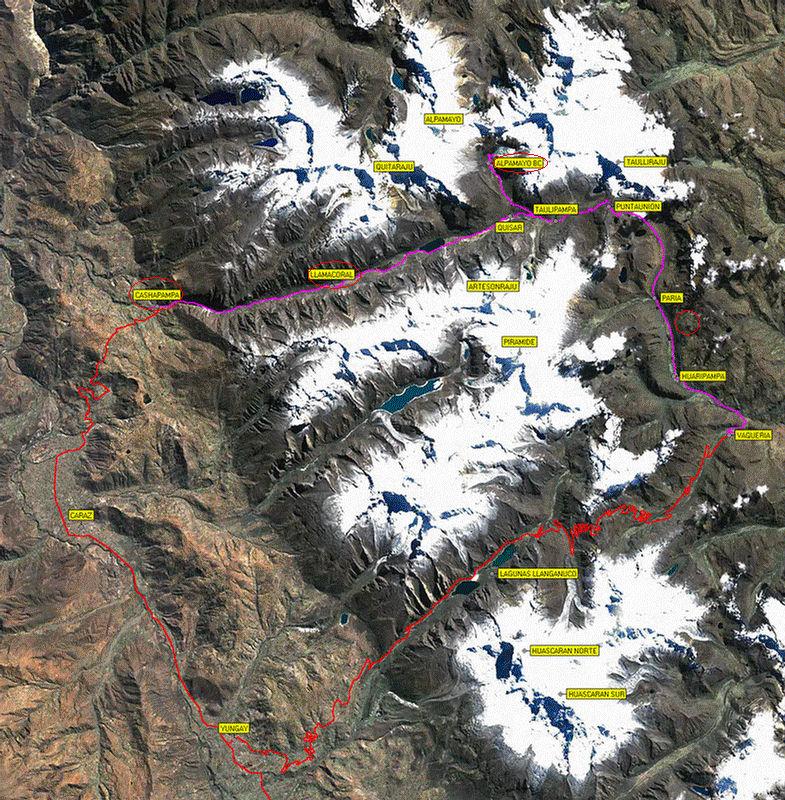

The Huascarán park contains 16 peaks higher than 6000m of the cordillera blanca which is the world’s highest mountain range out of Asia. I could not resist the temptation to traverse it on the splendid St. Cruz Trek, which for four days (and three camping nights) crosses its northern part and offers beautiful views on the main summits.

The colectivo to the starting point Cashapampa was fully occupied: 3 persons in the front row next to the driver, 4 persons in the middle row and one older lady among the luggage in the trunk. Carrying the heavy bagpack stuffed with camping equipment, warm clothing and food for 4-5 days, walking becomes another category: move slow and carefully watch every step, since a twisted ankle may become a severe problem in this remote wilderness. Luckily, the route climbs moderately for two days up to the mountain pass Punta Unión at 4750m and descends with some ups and downs to Vaquería at 3700m. In the first night, at a nice camping spot near a river, I met the colombian mountaineer José and the swiss couple Aline & Cédric, both cyclists as well, and we continued the trek together. The second day led us through a nice sand plane up to a camp site at the foot of the Alpamayo, dubbed „the most beautiful mountain of the world“. It was indeed an impressive view even from the southern, less glacially side, but as soon as the sun disappeared behind the ridge, I slipped into the sleeping bag, out of the cold. The next day was a long hike of about 10 hours over the highest point of the trek (unfortunably a very clouded view) and down to the sweet valley of the Río Huaripampa. During the night, I was caught out of the sudden by a heavy diarrea which made the normally easy 5hours-walk to Vaqueriá the next day a hard tour. With two pills of immodium (many thanks Aline!), I survived the 4 hours ride in the again very cramped colectivo back to Caraz: the road was rough but beautifully passed the icy mountain Huascarán (6768m) and the Lagunas Llanganuco. When arriving Caraz, I felt like Messner must have felt when coming from Mt.Everest: back to the pleasance of civilisation, a shower, a good meal and the satisfaction of a great experience.

In the meanwhile, Germany had made its choice between an uninspired chancellor and a fen fire on the ego trip.

Copyright by mcsa.org.za